It's Lonely Down Here Where the Holiness Grows

The Bible says some part of me is already seated in the heavenlies, but I can tell that these clay legs of mine, at least, are still stuck down in the mud. It's lonely and scary down here, and sometimes I'm tempted to find some sort of emotional release. However, like most cowards, I bend the rules instead of flat out breaking them, hoping to minimize danger.

I sin carefully because I'm too much of a wimp to take the big risks. If something I want to do might go nuclear, I tone it down a few notches. I won't steal, but I will covet. I won't divorce, but I will check out of my relationship emotionally when it wears me out. I won't murder, but I will hate.

I'm not (at least so far) the sort of person who commits the grand dirty whamboozie that lands a Christian in the hypocrite section of the evening news, but don't be impressed by that. To look for the grey areas is its own sort of sinister darkness, and to be in darkness at all is to be out of communion, for there is only light in the presence of God. His light is a jealous light that burns away distractions, and so here and there I become Eve sneaking a poisoned pear in the shadows.

But in the middle of the night, in moments when I am alone and quiet, I can feel the disparity between my present life and the comprehensive renovation that Jesus intends for me. I will catch a flicker of submission and long like Hwin to be consumed by God until I get back into the whir of the mundane, where I lose clarity. There is such clutter and noise all around me, and so few people seem to care about a radical sort of obedience that only a fool would chase if Christ isn't real.

The consuming faith of Bonhoeffer and Corrie ten Boom has been replaced with Ann Lamont's brazen, poetic excuses for faith-ish-ness. Hip, thinking believers have learned to call issues of personal morality "complex," and then deftly switch the conversation to social justice. Why? Because it's a heck of a lot easier to build a school in a third world country than it is to wait for healthy, holy intimacy in a lonely life.

I've tried to talk about this with a few of my more progressive friends, but I can tell they they think I'm just not insightful enough. They think I haven't read the right books or experienced the right heartbreak yet. They think I just don't understand how sex with the right people can be healing. They think I'm too closed-minded to see how this shared wonder is in itself an act of grace, no matter how it is obtained.

And maybe there are things I don't understand. I have been hurt in some ways, but not in all ways. What I do understand is temptation. I know how a thousand sweet excuses come in the goblin market cart, and I know how eager I can be to find a glorious reason to do a selfish, terrible thing.

I also know that my generation feels no shame about being consumeristic. When we were teenagers we were sold on a promise that doing God's will would make our lives happy. That's why so many of us were willing to worship him in the first place. But now culture is changing, and it's looking more like faith might mean deaths of a hundred sorts, so (feeling cheated) we defy God's right to determine our rights.

When he doesn't meet our demands in a timely fashion, when loving him hurts, we justify stealing. Then, when stealing doesn't work, we sulk over our breakups and bruises, licking our wounds, and blaming Him that He has let such darkness take over the earth.

In all of this we damage the community. There is so much talk these days about sex being a matter of two grown individuals making a decision, but it doesn't work that way in reality. Even private sex has communal effects. I disagree with Wendell Berry on many things, but I do love this excerpt:

"Lovers must not, like usurers, live for themselves alone. They must finally turn from their gaze at one another back toward the community. If they had only themselves to consider, lovers would not need to marry, but they must think of others and of other things. They say their vows to the community as much as to one another, and the community gathers around them to hear and to wish them well, on their behalf and its own. It gathers around them because it understands how necessary, how joyful, and how fearful this joining is. These lovers, pledging themselves to one another ‘until death,’ are giving themselves away, and they are joined by this as no law or contract could ever join them. Lovers, then, ‘die’ into their union with one another as a soul ‘dies’ into its union with God. And so here, at the very heart of community life, we find not something to sell as in the public market but this momentous giving. If the community cannot protect this giving, it can protect nothing—and our time is proving that this is so.”

Wendell Berry, Sex, Economy, Freedom and Community: Eight Essays (New York: Pantheon, 1993), 137-8.

When people we love and trust are involved in acts of betrayal, that hurts us, because they have betrayed us all. Community means we are all intertwined, helping one another toward heaven or to hell, and our secret duplicity feeds another's cynicism. We are all weakened by the weakness of one. Nothing we do in the privacy of a bedroom stays in the privacy of a bedroom. In one way or another, our hidden truth bleeds out.

I've been so deeply hurt by watching this lately; in fact I've been almost paralyzed with grief. And it's not just because I hate sin, but because I'm tempted to give up sometimes, too. When one of my friends decides to live a false life, my own temptations feel a little more unmanageable. I feel abandoned, sad, and discouraged about trying to wait on eternity for the results of my present sacrifices. All sorts of tapes start to play in my head, and it just gets so lonely holding white-knuckled to the truth in the dark.

This loneliness was choking me this week when I began to fall in love with George Herbert (1593-1633). Herbert is one of the metaphysical poets, but until a few days ago, whenever I've had time to explore that era of poetry, I've chosen to read John Donne instead. Donne is riskier and fleshier. He writes from the middle of the fight with his passions. I identify with him more easily, because I am more like him.

At first glance, Herbert seems to write from a place of resignation. I feel a hushed, settled reverence in his writing. He doesn't nail every line as powerfully as Donne, though he does offer some mighty images. However, the greatest aspect of Herbert's work that I have found so far is that he is not ashamed to love what is pure; in fact, he digs more rich beauty out of sincere devotion than I could have imagined possible... which reveals how terribly unimaginative I have been about devotion.

I fell in love with John Donne during that young stage of faith when believers are drawn to authenticity. But where one plants, another waters, and where Donne shows me that a Christian can be a vivid, red-blooded human in struggle, Herbert is showing me that there is an even sweeter beauty beyond that.

Too much that I've read in modern faith instruction stops at authenticity. I need writers who will move me past honesty into that fork in the road that forces me to chose between twisting my struggle into excuses or yielding my struggle to a gospel which empowers me to die the deaths of the new life.

- - -

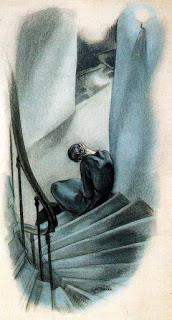

Art: "Loneliness" by Carlos Saenz de Tejada (1927)

I sin carefully because I'm too much of a wimp to take the big risks. If something I want to do might go nuclear, I tone it down a few notches. I won't steal, but I will covet. I won't divorce, but I will check out of my relationship emotionally when it wears me out. I won't murder, but I will hate.

I'm not (at least so far) the sort of person who commits the grand dirty whamboozie that lands a Christian in the hypocrite section of the evening news, but don't be impressed by that. To look for the grey areas is its own sort of sinister darkness, and to be in darkness at all is to be out of communion, for there is only light in the presence of God. His light is a jealous light that burns away distractions, and so here and there I become Eve sneaking a poisoned pear in the shadows.

But in the middle of the night, in moments when I am alone and quiet, I can feel the disparity between my present life and the comprehensive renovation that Jesus intends for me. I will catch a flicker of submission and long like Hwin to be consumed by God until I get back into the whir of the mundane, where I lose clarity. There is such clutter and noise all around me, and so few people seem to care about a radical sort of obedience that only a fool would chase if Christ isn't real.

The consuming faith of Bonhoeffer and Corrie ten Boom has been replaced with Ann Lamont's brazen, poetic excuses for faith-ish-ness. Hip, thinking believers have learned to call issues of personal morality "complex," and then deftly switch the conversation to social justice. Why? Because it's a heck of a lot easier to build a school in a third world country than it is to wait for healthy, holy intimacy in a lonely life.

I've tried to talk about this with a few of my more progressive friends, but I can tell they they think I'm just not insightful enough. They think I haven't read the right books or experienced the right heartbreak yet. They think I just don't understand how sex with the right people can be healing. They think I'm too closed-minded to see how this shared wonder is in itself an act of grace, no matter how it is obtained.

And maybe there are things I don't understand. I have been hurt in some ways, but not in all ways. What I do understand is temptation. I know how a thousand sweet excuses come in the goblin market cart, and I know how eager I can be to find a glorious reason to do a selfish, terrible thing.

I also know that my generation feels no shame about being consumeristic. When we were teenagers we were sold on a promise that doing God's will would make our lives happy. That's why so many of us were willing to worship him in the first place. But now culture is changing, and it's looking more like faith might mean deaths of a hundred sorts, so (feeling cheated) we defy God's right to determine our rights.

When he doesn't meet our demands in a timely fashion, when loving him hurts, we justify stealing. Then, when stealing doesn't work, we sulk over our breakups and bruises, licking our wounds, and blaming Him that He has let such darkness take over the earth.

In all of this we damage the community. There is so much talk these days about sex being a matter of two grown individuals making a decision, but it doesn't work that way in reality. Even private sex has communal effects. I disagree with Wendell Berry on many things, but I do love this excerpt:

"Lovers must not, like usurers, live for themselves alone. They must finally turn from their gaze at one another back toward the community. If they had only themselves to consider, lovers would not need to marry, but they must think of others and of other things. They say their vows to the community as much as to one another, and the community gathers around them to hear and to wish them well, on their behalf and its own. It gathers around them because it understands how necessary, how joyful, and how fearful this joining is. These lovers, pledging themselves to one another ‘until death,’ are giving themselves away, and they are joined by this as no law or contract could ever join them. Lovers, then, ‘die’ into their union with one another as a soul ‘dies’ into its union with God. And so here, at the very heart of community life, we find not something to sell as in the public market but this momentous giving. If the community cannot protect this giving, it can protect nothing—and our time is proving that this is so.”

Wendell Berry, Sex, Economy, Freedom and Community: Eight Essays (New York: Pantheon, 1993), 137-8.

When people we love and trust are involved in acts of betrayal, that hurts us, because they have betrayed us all. Community means we are all intertwined, helping one another toward heaven or to hell, and our secret duplicity feeds another's cynicism. We are all weakened by the weakness of one. Nothing we do in the privacy of a bedroom stays in the privacy of a bedroom. In one way or another, our hidden truth bleeds out.

I've been so deeply hurt by watching this lately; in fact I've been almost paralyzed with grief. And it's not just because I hate sin, but because I'm tempted to give up sometimes, too. When one of my friends decides to live a false life, my own temptations feel a little more unmanageable. I feel abandoned, sad, and discouraged about trying to wait on eternity for the results of my present sacrifices. All sorts of tapes start to play in my head, and it just gets so lonely holding white-knuckled to the truth in the dark.

This loneliness was choking me this week when I began to fall in love with George Herbert (1593-1633). Herbert is one of the metaphysical poets, but until a few days ago, whenever I've had time to explore that era of poetry, I've chosen to read John Donne instead. Donne is riskier and fleshier. He writes from the middle of the fight with his passions. I identify with him more easily, because I am more like him.

At first glance, Herbert seems to write from a place of resignation. I feel a hushed, settled reverence in his writing. He doesn't nail every line as powerfully as Donne, though he does offer some mighty images. However, the greatest aspect of Herbert's work that I have found so far is that he is not ashamed to love what is pure; in fact, he digs more rich beauty out of sincere devotion than I could have imagined possible... which reveals how terribly unimaginative I have been about devotion.

I fell in love with John Donne during that young stage of faith when believers are drawn to authenticity. But where one plants, another waters, and where Donne shows me that a Christian can be a vivid, red-blooded human in struggle, Herbert is showing me that there is an even sweeter beauty beyond that.

Too much that I've read in modern faith instruction stops at authenticity. I need writers who will move me past honesty into that fork in the road that forces me to chose between twisting my struggle into excuses or yielding my struggle to a gospel which empowers me to die the deaths of the new life.

- - -

Art: "Loneliness" by Carlos Saenz de Tejada (1927)