Addiction to an Imagined World

Most people have an addiction of some sort: the internet, drugs, alcohol, food, anger, porn. Something to take the edge off the pain of getting stuck here.

My addiction is imagining an impossible ideal.

Sounds fake, but it’s absolutely not. My struggle is just as ugly and just as dangerous as anything I listed above.

Here’s how it works.

I live life with you in a real world. I love and tend the people before me. I fight for causes. I create in a tactile way. But I do all this with a backup life. I’m always keeping one or two lines open to an imaginary second reality where I can retreat when existence gets too heavy and too hard.

When I’m so lonely I can barely move, I go into the “What if these factors were different?” zone. And I let those possibilities create an alternate reality—then I begin to walk toward it and sink into it.

There’s a scene in the movie Inception in which a room full of elderly dream addicts confuse real existence with their ideal communal dreams. They begin to see dreaming as primary and reality as secondary. And I can do that, too.

I don’t walk around drunk. I’m not hooking up with strangers on the sly. My BMI is super healthy. But internally, I run away.

And just like you don’t see the consequences of other addictions immediately, the long-term harm of “ideal addiction” only reveals itself over time.

If you are INFJ or INFP, our kin are particularly notorious for believing that “the ideal” is out there somewhere—we just need to find it. That impulse is what makes movies like Amelie charming or writing like “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” relatable. But what looks sweet or human in art can get pretty ugly in real life.

Giggly infatuation with a witty, electric (though totally scripted) Pimpernel/Mauguerite dialogue can slowly form into a feeling of entitlement. We can start to believe, “My life is boring and empty. I deserve similar banter. Unless I have what I can imagine, I am dead inside.”

This resentful ache can grow inside until INF’s can begin to feel hopeless—until they spend a lot of the day checked out emotionally—until they stop trying to engage—until they survive by quietly tolerating.

As a result, gratitude disappears. True vulnerability retreats. We start to become impossible to truly know—which drives us further into the dream.

When I was much, much younger, B and I were having a pretty hard time of marriage. I won’t go into the details, but there were legitimate reasons for both of us to be tired and frustrated.

In the midst of this struggle, I received a piece of writing from a male friend. It was powerful and nuanced, and it seemed to indicate tenderness toward me that took my breath away. I felt those words wash over me. I walked two miles holding it in my hands. I thought back over many, many other instances in which this person had laughed with me, worked with me, connected with me.

And as I reflected on all of this, and as I considered how hard things were at home, I sank into an all-consuming “What if?” That daydream was exciting and overwhelming, and I let this new, imaginary second world carry me for several DAYS while externally doing the tasks I needed to do to serve my family.

Finally, I had to tell B what I was struggling with. As mad as I was at him, I just couldn’t carry it alone. Slowly, this alternate reality died down into nothing. But over and again in my life, similar situations have occurred. And it hasn’t just hit in romance—this has happened in friendships, in work, in calling—in weird dreams about running off and creating a whole new life.

It can be triggered by blogs from wanderers and rebels. Blogs from artists and free spirits. People who live elsewhere doing better things than I do. People who have “the life I can only dream about.”

Today our family had a pretty big scare. I won’t go into the details, but I will say that for about three hours, I was thrown into a severe awareness that my painfully boring, everyday life is actually pretty, stinking beautiful.

During this event, my physical state was vulnerable—I was (literally) in the middle of an Appalachian forest, on a trail that was scary and empty, with only a kid beside me that I knew I couldn’t fully protect. I was looking for someone I couldn’t find and had no way of finding. And I was afraid this person was in danger.

At that moment, reality was acute and severe. I gripped my Mace, hoping for the best in the men who occasionally approached us. My legs shook with the rigor of the path—one incline was nearly straight up for perhaps 1/4 of a mile. My legs were trembling with fatigue, my heart was pounding, and I thought my lungs were going to explode. I didn’t know if tragedy awaited. And I couldn’t stop.

The severity of that situation pushed me to talk to God like I haven’t in a long while. As I did so, I realized I’ve been kind of avoiding him— at least I’ve been avoiding certain conversations with him—because I’ve been angry that reality and my ideal don’t line up in some serious ways.

Strangely, in the hours leading up to this event, a friend had made me watch an interview with Eugene Peterson and Bono. As those two men talked about the Psalms, I realized that I have not made space to be emotionally present with God.

When I’ve been lonely, I haven’t written those severe feelings in honest appeals to the Lord. Instead, I’ve run into my imagination to medicate with fabricated impossibilities.

When I’ve felt doubt because of the duplicity of Christians in the world, I haven’t written those tremors to the Lord. I’ve run to humans (real and imaginary) and tried to find security in them instead.

Something about being out in the middle of a vast wood, panting, scared, trembling, weak stripped all that away. Imagination was no comfort in severity.

It was a terrible experience. It was also a critical experience.

Tonight I’ve been thinking a lot about the reality Jesus chose for his 33 years on planet earth. I’ve thought about the irritating people he found as companions.

Jesus was the one person who didn’t have to imagine the ideal—because he had been inside of it always. He knew utter perfection.

Then suddenly, he was thrown in the middle of a superstitious, disappointing lot of yahoos who couldn’t provide him any sort of true intellectual or spiritual companionship. People were stinky, greedy, messy, dumb. Local scenery was just meh. (At least from my perspective.)

And Jesus didn’t even wait until an era in which humans understood the scientific advances he’d planted into the world. He showed up smack in the middle of primitive life.

These were the people he loved and served every day.

To get the strength for this, he prayed. He was honest with the Father.

Then he went into reality, believing those slow, uninteresting people he would encounter weren’t just secondary citizens but an exact selection of souls he was supposed to know face-to-face inside the whole of human history.

These were not the elite. Not the powerful. Not the witty. Not the stuff of dreams, but the stuff of fish boats and dusty roads. These were people who missed punchlines. People who dreamt small. People who wanted a free meal when the Bread of Life was walking in their midst.

“Who do I think I am?”

It clanged like a gong inside my chest after the crisis was over.

“Why am I so unwilling to be fully present?”

My addiction to imagining the ideal has sucked away so many psalms I’m way past due writing.

I’m falling asleep tonight feeling a little shy about that. Also, I’m a little excited that tomorrow would be a good day to start writing them.

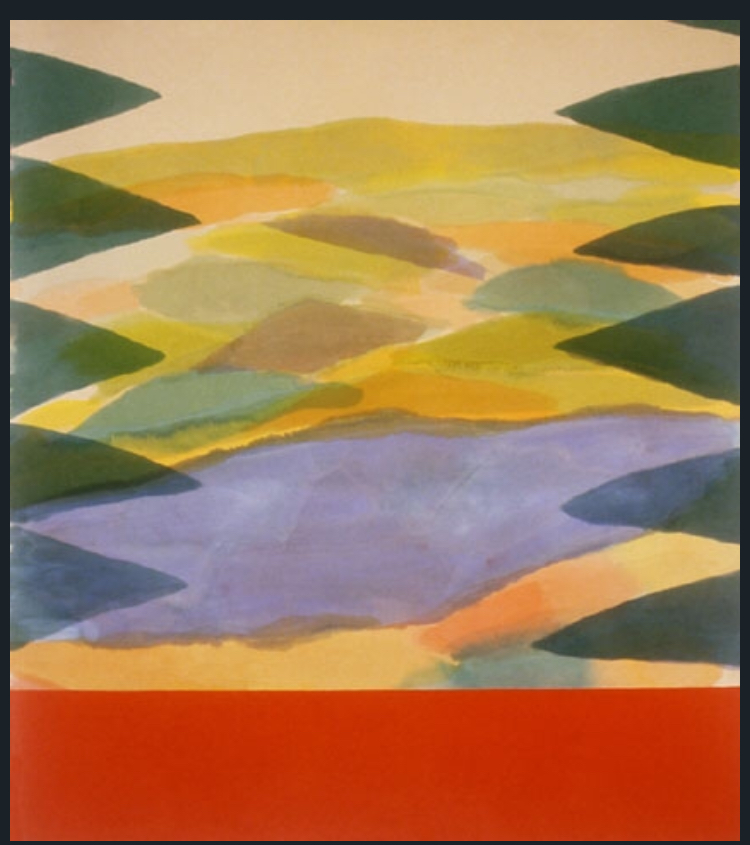

“Imagination’s Door” by Ronnie Landfield