Trickle-Down Theology

Catacomb of Priscilla, Rome

Most of us aren't college professors, so we don't get paid to study. We have to squeeze in Biblical research wherever we can find the time for it.

This morning, I wanted to double check an assumption about the bloodline of Mary, but I only had an hour or so to find what I needed. The assumption? That Mary was connected to the line of Levi on her mother’s side (because she was related to Elizabeth), and to the line of Judah on her father’s side (because the angel Gabriel told the virgin that her son would be Davidic).

The thought of Mary’s lineage deriving from both priests (Levi) and kings (Judah) seems to fit in so many ways. When I think about who Jesus was, and how he connected the old covenant to the new, this feels like the sort of nuance the Father would choose when selecting a mother for his Son. But feelings don't make truth, so I needed facts.

Anyway, I have an hour to figure this problem out...kid is waking upstairs, I have a long to-do list... and as I was studying, I ran into a dilemma Christians (and atheists) have been talking about for years: the genealogies of Matthew and Luke list two different fathers for Joseph.

Matthew tells us a man named Jacob (not Isaac’s son) was Joseph’s father while Luke tells us Heli held that role. Historical and cultural reasons explain why the Bible diverges here--reasons that would have been obvious to first century readers thinking in terms of legal and biological lines of descent. But any time you find a seeming paradox in the Bible, you’re also probably going to find human conflict about it. And that's what I ran into this morning.

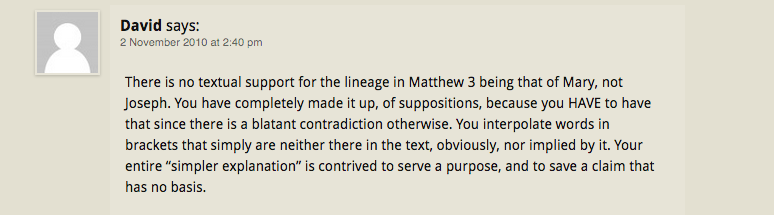

For example, here are two comments I found at the bottom of a website wrestling with Joseph’s parentage. I want you to notice the posture of these two readers.

Both “David” and “Soul Collector” are condescending, dismissive, and rude. The first assumes dishonest motives in the writer. The second spits out a haughty, “Do some research,” despite the fact that the original post is research based.

Even though I’m forty-six and have been studying theology for over twenty years, my stomach still feels sick when I find myself in “Christian” dialogues like these. I had a sincere question, and I was looking for a solid answer. I had very little time to find what I needed. But instead of being encouraged by the body, I felt beat up by it.

I don’t want to be part of a community that engages this way. There’s no kindness here. There’s no room for curiosity. There’s no room to be in process.

So I started thinking about where this sort of bravado begins. And I started wondering how we might help it stop.

At the highest levels of Christian research, scholars have long bantered back and forth about interpretation. In those contexts, a fraternal volley can be served and returned with a certain measure of humor. It’s how the game of discovery is played because the best scholars are inherently Socratic. They challenge and they debate, trusting the best ideas to rise to the surface.

The camaraderie of intellectual volley is everyday fare inside of a university setting. After a rousing match of wit, two profs can go have lunch together. No blood, no foul. But what happens when these internal debates overflow into lay culture? And in light of this, what responsibility do Christian scholars have for the posture they adopt inside of academia?

I’ve read elite theologians who walk in a sober understanding of the responsibility they hold to the non-scholastic world. These men are not only theologically accurate, they also teach with a posture that embodies the gospel—a posture that is “caught” affectively and intuitively mimicked through the church.

Others, however, seem more myopic. They get stuck inside of an academic bubble and live accordingly. A campus is a biosphere, after all, which is beautiful and also dangerous. It’s easy for a professor to get wrapped up in the rush of publications, in the electricity of the classroom, in theories, in faculty politics, in forums, in the quest for tenure—forgetting that what happens inside of academia automatically trickles down into something very different outside of it.

Non-academic readers read academic writings, and they mimic a theologian’s posture--even when they can’t comprehend his intended context. This has a huge impact on dialogue within lay Christianity.

I wonder what those scholars would change if they could see what happens with their teachings down here in the lower church—a realm where tertiary and quaternary disciples break fragments of academic wit into shards and use them as real weapons to hurt real people? What would they change if they could see how two-decades-worth of careful, primary source research eventually morph into a cocky online smack down by AmillTom542 who blasts, “DO SOME RESEARCH!” in a public forum?

Can anything be done inside of our elite havens of discovery and discussion to help heal the church—not just intellectually, but also relationally?

This morning, my husband was praising Derek Kidner's commentary on the Psalms. “This is a guy who hasn’t just studied the text—he’s let it change who he is,” B said.

I’m already enchanted. I can feel the gospel radiating off my husband after he’s read Kidner. This is the impact of a scholar who operates like a shepherd/teacher. This is the impact of an intellectual who writes confessionally instead of just correctively.