The Smell of a Dead Monk

Father Zossima is the kind old monk in Dostoevsky’s The Brother’s Karamazov. He’s similar to Bishop Myriel in Les Mis, an otherworldly sage who has learned to live out the gospel in a radical way.

Father Zossima is also the beloved spiritual mentor of Alyosha, the hero of the novel and the youngest of the three Karamazov brothers. Aloysha is only twenty, and he’s a novice in the local monastery, so he trusts Father Zossima wholeheartedly, agreeing to follow whatever instruction the old man gives. Because Aloysha’s biological father has been distant for most of his life, it’s easy to see why this young man gravitates toward kindly, paternal affection.

Father Zossima is also a local celebrity, known for spiritual access to healing and prophecy. It’s widely suspected that the old man will be sainted when he dies, so when his earthly life finally draws to a close, the townspeople grow to a frenzy. Expecting miracles, they bring family members who need healing to his coffin.

Yet at this critical moment in the novel, something terrible and unexpected happens—something which shakes Alyosha’s faith. Father Zossima’s body begins to decay.

At the time, tradition taught that a true saint’s body wouldn’t decompose—that it would even release a perfumed sweetness into the air. Yet within hours—even sooner than most—the scent of real, human death fills the room.

Several monks who had been jealous of Zossima’s fame and admiration seized this opportunity to mock and deride him. Soon, their whispers grew to open verbal hostility, and finally a hateful monk enters the mourning room to lambast the dead father as a false teacher.

Alyosha’s naïve young heart breaks.

He had not only loved the old man, he had lived inside a bubble of spiritual idealism, believing a string of religious fairy tales. When reality didn’t match his expectations, Alyosha was spiritually undone, overcome with doubt, devastated that all had not gone as he expected.

I read this section of Karamazov after midnight last night. I read because I couldn’t sleep because I was worrying. Though God tells us not to fear, I was afraid.

Beside me, my husband groaned in his sleep. He hurt his back pretty badly yesterday, and of all the times that injury could have happened to our family, this is one of the worst. Yesterday was our first day of switching to a new insurance with a new deductible, and after several nervous hours of Googling bulging and ruptured discs, I was trying to decide whether he needed an MRI.

For some of you, hits like this never seem to stop. There’s always one more kink in the happily ever after.

Even if you’ve never believed in the prosperity gospel, the theological promises of movies like Facing the Giants get into our bones. In the back of our hearts, we still expect faithful resignation to be blessed in visible ways. The follower of Jesus will coach the team to winning the championship, snag the new pickup truck, get the baby, and look at last around at his mortal life and find that all is well.

Some stories of faith certainly look like this, but in others, the blessings of God may smell more like a dead monk. That’s because God knows what each of his followers needs (truly needs), and his love allows different challenges for different Christians. He knows that coming face-to-face with deep disappointment can be critical to the maturity of faith.

As Alyosha comes to terms with the smell of death in his mentor, he faces, “a crisis and turning-point in his spiritual development, giving a shock to his intellect.” Perhaps you’ve lived out a similar shock—perhaps you know what questions rise when we realize that God’s behavior does not fit into the tiny boxes we have made to hold Him. These moments of reorientation may be painful and bitter, and we may weep for days when we face them. But like Alyosha, they can also grow us up.

By his deepest disappointment, by this brutal blow to the crux of his security and idealism, Alyosha faith was strengthened. Because of the pain of a lost ideal, his belief was given a "definite aim.”

As I prayed this morning, I felt the onslaught of challenges facing our family. I prayed for direction. I prayed for sustenance and for miracles. I also prayed for the ability to worship God in rooms that reek of death.

On June 8, a team of scientists from Oxford published research addressing the Fermi paradox, the gap between our expectation that life exists somewhere in the universe and our inability to find it. This study concludes that we cannot find extraterrestrial life because it doesn’t exist.

Since I haven’t seen the Bible specifically negate the possibility of alien life, this has never been a major theological battlefield for me. I’ve always trusted that an infinite God could have simultaneous narratives running in different solar systems (or even in different dimensions). I’ve supposed that if he did have something like that going on, all narratives would one day fold together into a lovely story he knows we can’t comprehend with tiny mortal minds.

I haven’t obsessed about it, of course; I haven’t actively believed that life did exist elsewhere. I’ve just held the possibility loosely. I’ve let what God left unsaid remain mysterious.

So, it was strange to read the Oxford study and consider the thought that humans might actually be alone in the universe. I stopped to really think about that--we could be the only beings anywhere with souls. In all of this everything that goes on seemingly forever, our capacity for worship could be unique.

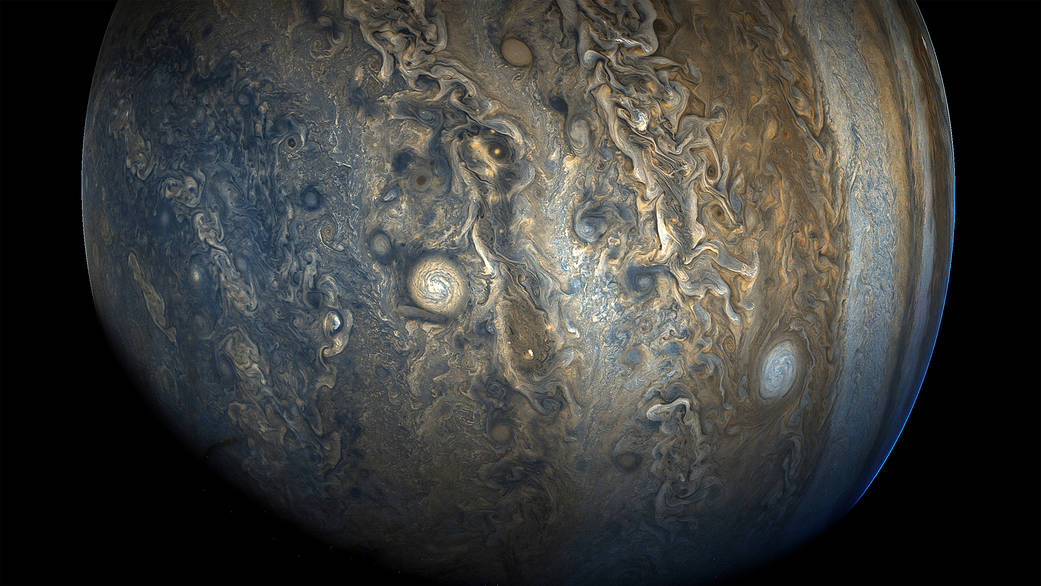

Maybe this won't hit you like it hits me--astronomy and I have kind of a "thing" going, and we have for a while. It’s more of a romance than an academic passion. I’m one of those weirdos who cries real tears when NASA releases new pics of Jupiter and Pluto. Star nebulae give me goose bumps. As a baby, my first sentence was, “The moon is in the sky, Mr. Hall.”

I have felt reverent awe for God’s artistry in the heavens every since I can remember, a sense of being pressed down to my knees by the all-I-am-not, a compression like gravity. The created order is so beautiful, so extravagant... I’m tempted to use the word “magical.”

Without that Oxford study, assuming that we could possibly be alone in all of this feels audacious. History has slapped the hand of the small-minded church too many times. My faith is post Copernicus, post Galileo—I don’t have geocentric impulses.

And yet, here is science telling me that we could be alone.

I wasn't expecting to be taken so seriously by my Creator.

What if He really did make all of this--the dimension of time--the capacity for sentience--the ability to praise--all poured into a handful of creatures placed on one tiny, tumbling rock? What if our hymns are the only hymns besides those songs the angels sing?

The circumstances which seem so grave to me--the challenges that make my belly quiver and my knees shake--readjust in light of this possibility.

My pain and fear are portals in all of space and time, and even when I face the smell of the decomposition of my theological fairy tales, I still stand before the God who was, and who is, and who always will be.

Here in the silence of the created order, I can speak trust to Him. I can yield to Him. Among all the cold rocks and the fiery gasses of all of creation, I have been given the capacity to hold my arms wide before all his mysteries and confess:

I did not see you lay the foundation of the earth.

I did not determine its measurements.

I do not know how its bases were sunk,

or who laid its cornerstone,

when the morning stars sang together

and all the sons of God shouted for joy.

I did not see you shut in the sea with doors

when it burst out from the womb,

I was not there when you made clouds its garment

and thick darkness its swaddling band,

and prescribed limits for it

and set bars and doors,

saying “Thus far shall you come, and no farther,

and here shall your proud waves be stayed.”

I have never commanded the morning since my days began,

or caused the dawn to know its place.

I have never changed its surfaces

l like clay under the seal,

or dressed the earth like a garment.

I have never entered into the springs of the sea,

or walked in the recesses of the deep.

I have never seen the gates of death or the gates of deep darkness.

I cannot comprehend the expanse of the earth.

Only by your hand, do I know the way to the dwelling of light,

because you are the Light of the World,

and amid all of the lesser lights of all You have made,

you, Great Light, have come to give light to me.

While a soulless Jupiter storms, while distant stars implode, while the red dust of Mars holds low in a lifeless hush, while no-man of the moon paints every grass tip silver, I can recline upon Jesus.

No matter what happens in my life, He is worthy. Though the good, dead monk reeks, Christ remains a center which cannot be shaken. And He has given me a voice that is able to praise Him. Thanks be to God.