The Foolbearers (Genesis 1: 3-8)

"And God said, Let there be light: and there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness. And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And the evening and the morning were the first day. And God said, Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters. And God made the firmament, and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament: and it was so. And God called the firmament Heaven. And the evening and the morning were the second day."

(Genesis 1:3-8, KJV)

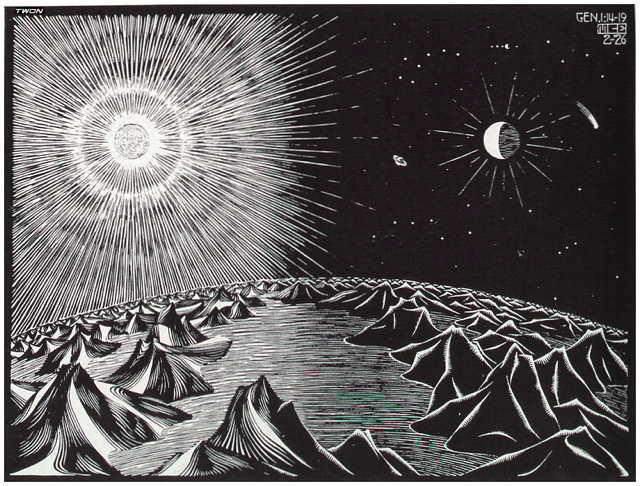

by M.C. Escher

A subtle but fascinating distinction occurs in these six verses.

After God created the light, he “saw” that it was good. Does this mean God had a sudden realization? Of course not. This Hebrew verb connotes certification. It shows us that whatever God declares a thing to be determines what it actually is.

God's division begins with the obvious. Light and dark are different, and light is good. Who would disagree? Who confuses day and night? Then He ups the ante.

“And God said, “Let there be an expanse in the midst of the waters, and let it separate the waters from the waters.” (ESV)

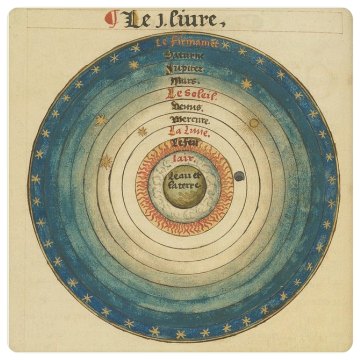

The Hebrew concept conveyed by the word "expanse" (raqia) isn't common in our era. I actually prefer the bolder term chosen by the translators of The King James--“firmament”-- because it connotes solidity like a sheet of gold stamped into a physical arch. This term harkens back to an ancient mode of perceiving the universe, a primitive belief that a solid barrier held the upper realms apart from the lower realms.

Moderns are sometimes embarrassed about this part of Genesis because we know that the concept isn't scientific--a hard, physical boundary does not separate atmosphere from space. In fact, Young Earth Creationists try to get out of this pickle by arguing that the Septuagint was influenced by Egyptian cosmology, which influenced Jerome. I find this posture self-contradictory and desperate--a distortion of the Word of God driven by eisegesis.

It's strange that conservatives could fall into the eisegesis trap when they are trying to be faithful to the text, but this mistake happens so easily. Most of us don't realize that when the Space Race of the 1950's shifted the values of American public education, our nation began to elevate physical sciences above the humanities. America needed schools to produce scientists so that we could maintain global dominance, so the epistemological values of our nation shifted. Instead of looking to rational or philosophical principles to answer the question, "What is most true?," validation moved to the empirical sciences.

Readily, the church embraced the secular culture's values--if science was most important to America, Christianity would find a way to make the Bible scientific. Instead of letting the text lead, Christian scientists began to ravage the Scriptures, defying principles of literary interpretation and genre because they were intent on maneuvering the Bible to help win culture wars.

What I think they failed to realize is that far more convicting truths can be gained by letting these verses be what they naturally are, inside of the genre and language that God gave us--even if that leaves some tension with secular values/epistemological systems. Accepting the inspired word inside of its own narrative context may not allow us to beat our chests in Bill Nye's face, but it can lead us to mighty, God-given, soul applications than are far more likely to renovate our nation by the Spirit of the Living God than piddling around with culture wars.

A "conservative" should never believe that he is doing something noble when he reorients Scripture to accommodate the epistemological systems of humanism. es, many principles of science were hidden inside the Bible thousands of years before humans discovered them. But when we are driven by fear or insecurity--needing Genesis to operate like a scientific manual so that we can fight the atheists, we have become idolators. Our utmost goal with the Bible should be glorification and enjoyment of a holy God which leads us to union and obedience.If we focus on this, the rest of the work God has prepared for us (Ephesians 2:10) will fall into place.

Looking closely at the actual text of Genesis 1, verse 7 repeats the Hebrew word for “divide”--the same word used a few sentences earlier to divide light from darkness. This time, however, God is dividing LIKE THINGS—“water” from “water.” The Hebrew term used here can mean water (as we know it), or it can indicate other liquids like urine, semen, or any juice of any substance.

In his previous act of Creation, God created a distinction between entities that are obviously different—light and darkness. In this section, however, he draws a firm boundary between entities that seem similar to human eyes: the waters above and the waters below. God creates a firm (even as solid as hammered metal) separation between what seems identical to us.

I find this passage breathtaking in a world like ours.

Even non-believers are usually comfortable with light/dark moral distinctions that seem obvious. Don’t murder. Don’t steal. These issues are generally as clear as day and night. Who wouldn't agree?

But what do we do with a God who creates a separation between choices that feel morally similar in a relativistic world? What if a holy God decides to make a moral boundary as firm as metal arch, dividing choice from choice? What if he says, “This fruit you may eat,” and “This fruit you may not.” What then?

In these two first acts of creation, we find a scenario more powerful (humbling, convicting) than any empirical, scientific claim. We are given two images that reveal the extent of God's authority--a theme which repeats again and again throughout the remainder of the Bible.

In chapter 24 of The Call, Os Guinness describes “the foolbearer,” as a Christian who is willing to embrace God’s definitions for good and evil in the midst of a relativistic world. Guinness writes that “sin” is “the claim to the right to myself”—and therefore “the claim to my right to my view of things.”

The progressive American church wrangles over the delicate moral dilemmas of our time as if defining sin is sort of new challenge for the modern man, but believing that humans are bright enough to redefine good and evil isn’t new. From the very first chapters of the Bible, we find Eve facing a temptation to trust her own judgment, opting for her own definition of good over God’s.

The forbidden fruit looks good to her—according to the workings of her mind and the evaluation of her own senses. As far as we can tell there’s nothing the least bit empirical or rational about God’s command to stay away from it. So when the serpent asks, “Has God really said?” Eve decides to trust her own gut instead—finding a way to chase goodness that doesn’t involve yielding to God’s authority.

She was unwilling to trust the foolishness of God over the wisdom of man. I have been, too. So many times.

This is not a call to "flagrant anti-intellectualism"--the "Credo quia absurdum ('I believe because it is absurd')" (Guinness 206). However, it does involve active submission to a Messiah who said, "Not my will but Thine." And I think that many progressives fail to admit that this sort of compliance is likely to be costly, for this Messiah also said that those who wanted to save their lives would need to lose them first.

So when I read this section of Genesis, I find myself struggling at the pinch of it before I find myself resigned. Genesis 1:3-8 reminds me that I sit before a God who has the authority to divide the world into categories that may or may not always align with my human reason.

Most of the time, God seems to say, "Light and darkness are different, and the light is good." Most of the time, his declarations seem rational to me, so I readily agree with them. But are other times when he divides water from water with a solid boundary, and his logic feels obscure and difficult. There are times when he calls a division "good," that I call baffling.

"Here is the fruit, Eve. I say don't eat it. What will you do with that?

"...when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate."

I get that choice. Sadly, I make it every day.

Luke 1 shows us two different personality types standing in the intersection of the holy mysterious. Zacharias the cynic hardened and Mary the simple softened, though the risk of her faith was far greater. Almost immediately she yielded: "Behold, I am the servant of the Lord; let it be to me according to your word.”

She is the anti-Eve, the willing foolbearer, who opens like a flower in the presence of the sun. Simple people like Mary may not make a big splash in the culture wars. They may not build a giant ark or stand on a university stage debating Richard Dawkins while trying to save America.

But in some hidden, lower-class bedroom, a Mary might stand toe-to-toe with the realization that a scientifically-impossible pregnancy will cause everybody she knows to think she's either bat crazy or a lying slut. She will know how much faith is likely to cost and yet resign the womb of her soul to a living God with a whispered, "Not my will, but Thine."