Reading Eugene Peterson's The Message

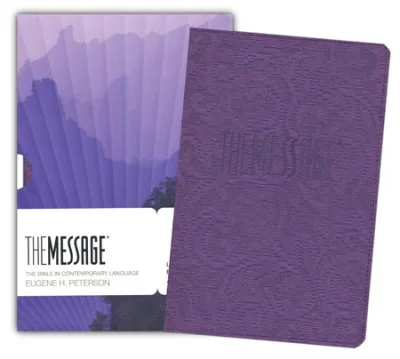

Yesterday I received a gift copy of Eugene Peterson’s paraphrase of the Bible, The Message. I cracked it open to the book of Micah last night, then I read back through that section this morning. It was good medicine for my heart during these crazy times.

As I was reading, I realized that I wanted to write a post explaining how I use this variation of God’s Word. While growing up inside conservative Christianity, I heard some pretty strong, negative opinions about The Message. Teachers told me that this was the version "serious Biblical scholars didn't use," and it was often regarded with either suspicion or outright disdain.

But in retrospect, those opinions weren't limited to Peterson’s work. During my lifetime, in my particular circles of evangelicalism, the debate about “which Bible to use” has spanned translations ranging from the NIV through the HCSV. Every few years while I was growing up, it seemed like an expert came along to scold us for reading whatever we were reading, and then tell us which translation of the Bible to use instead.

So I'd like to take a few minutes to explain why Biblical translation is even an issue, first. Then, I'd like to get into why I love The Message, and how I tend to use it in my walk with Jesus.

As I understand it, the primary translation dilemma (for all versions) tends to boil down to a choice between a word-for-word translation or a thought-for-thought translation. For example, let's imagine translating an English idiom into another language. If I told you that my neighbor, Bob, had a “chip on his shoulder,” you would understand that I meant he was resentful and looking for ways to be offended. But how would I translate that idea so that someone from another country understood it? Would I choose a word-for-word replacement? Would I say, “My neighbor, Bob, has a massive piece of flesh missing from his right shoulder”? Or would I take that same idea and find words or phrases to help someone who doesn’t know English idioms understand what I actually meant?

In my decades of conservative Bible study, I often heard people arguing that one translation or another was "closer to the text." However, I rarely heard people explain the technical difficulty of decisions translators had to face. Some of these choices aren't easy.

During my Precept Study Bible years, I used the NASB because it was supposed to be a solid attempt at literality while helping students with phrases that didn’t translate well into modern English. Also, notes provided literal translations for tricky passages, so that I could see what interpretative decisions had been made.

After the NASB, a lot of my crowd switched to the ESV. This is still the version I use, for the most part. It was first revised in 2007 and then again in 2011, mostly with attempts to replace archaic language with more modern phrasing. I’m not a huge fan of the revisions, but I don’t think they took any serious meaning away. In fact, here’s a link, if you want to check some of those changes out. ( http://static.esv.org/misc/esv_2011_changes.html ) My guess is that you will take a look and say, "What's the big deal?" Because really, the shifts are minimal. Word nerds like me would rather use “teem” than “increase greatly,” so my disappointment here is more aesthetic than theological.

Bible readers who embrace Dr. Mark Strauss’s frustrations with the ESV’s handling of various idioms and interpretational “errors” (http://zondervan.typepad.com/files/improvingesv2.pdf ) now seem to be smitten with the Holman Christian Standard Version. I like what I’ve read of the HCSV, but I still use the ESV for the bulk of my serious study. Why? Because I own ESV Bibles that I've already marked up, Bibles I'm familiar with that I like. When the time comes to buy a new study Bible, I'll do some research about which version to purchase. For now, I'm pretty happy with what I have.

I will say that I'm glad that (for the most part) the ESV doesn't seem to be quite as drunk as the (new) NIV on attempts at gender-neutrality. Yeah, there are a few places in the ESV where “brothers” and “men” are replaced with “people,” but God is still “He,” and for the most part, the original gender language is left in tact.

(BTW, can I just offer up a random opinion from a fierce, independent female? I don’t like it when Biblical translators or hymn revisionists assume that I’m not bright or strong enough to understand that I’m included in masculine pronouns or nouns. Gender words are not confusing cultural idioms, and I’m quite capable of navigating the Biblical gender waters without needing blow-up arm floaties. Likewise, changing God to a “she,” is ridiculous. God took care to include feminine references to himself in the Bible, too. We just need to let Him do what He intended to do in every description of Himself and stop messing with His art.)

Dedicating this picture of the botched up repair work of Martinez's 19th century fresco in Santuario de Misericordia to all those people who keep messing with Biblical gender language. Stop it, please. Thanks.

Students of literature tend to love the KJV for its Shakespearean language, despite a few technical issues here and there with translation. Whereas a good chunk of baby boomers (particularly the electric guitars and smoke machines contingency) poo-poo 16th-17th century diction, many young readers tend to revel in the reverence and balance of this old masterpiece. Our world has lost some of the majesty and reverence connoted in the King James Bible, so we delight to find it still exists somewhere. Artistically speaking, I imagine that this version will always be my favorite.

As much as I love the Bible, my biggest beef with modern access to God's Word is actually not found in the nuances of translation, but in the fact that the largest publisher of Bibles is owned by one of the most prolific pornographers in America. It disgusts me that Rupert Murdoch is making major money off God’s Word. The Bible is the best-selling book of all time. What in the heck are we doing pouring money into such channels?

This business union is a definite moral crisis in American Christianity, and I think believers need to find some way to stand up and remedy this problem. (FYI, my strong stance on this automatically limits my professional career as a published Christian writer. However, if it comes down to it, I would rather never publish books and face Jesus someday knowing that I worked to divorce His church from a connection to gross corruption. God's Word should not be yoked to supporting pornography in any shape, form, or fashion.)

But back to The Message...

If anyone other than Eugene Peterson had attempted The Message, I might feel differently about it, but Peterson is special. I love his writing, and I love his heart. I trust him deeply.

And when I read The Message, I’m not looking for a literal translation of the Bible. In fact, in my opinion, The Message is not a translation at all. That doesn't lessen it in my book. In fact, it increases its value to me.

To me, The Message is a paraphrase written by a dear, wise pastor. It is like a sermon delivered after years and years of study, one man’s understanding of a holy text, offered to his parishioners. This is how I use The Message. I don’t bring the same expectations to it that I bring to the ESV, NIV, KJV, or HCSV. I receive it as a homily from the mouth of a local chaplain, processing what I read as if I were sitting in a pew, listening to a human teacher talking about his week of study.

And just like I do when listening to an oral sermon, when I use The Message, I keep another translation open for reference. I do this because I want to look at a more literal rendition of Scripture while also listening to what Peterson gleaned from the text. Many times while doing this, I have seen a new angle on familiar parts of the Bible.

Good teaching pastors help a congregation catch the heart of a passage, and often The Message has done this for me. Sure, sometimes I find sections of The Message that I would have written differently, just like I often hear teaching pastors say things in a way that I wouldn't have said them. But because I am not expecting divine revelation here - because I let the tool be what it is (no more, no less) - I often come away from my time of engagement with The Message stronger in my faith.

I've talked with quite a few older believers who have hit a low point in faith at some point. (C.S. Lewis refers to these times as "troughs." Read about this here, if you are familiar with how The Screwtape Letters work. (The Screwtape Letters are letters from a fictional demon to his protege.)

Troughs are are seasons when the Bible grows familiar and faith feels heavy and dull, and I think The Message can be particularly helpful for this stage of life. While I might not recommend Peterson's paraphrase to every single non-Christian or new believer who is just beginning to learn essential Biblical truth (though I might recommend it to the more artistic searching sort) , I think The Message can be medicinal for weary, disillusioned Christians walking through a dark night of the soul.

I love Eugene Peterson, and I'm deeply grateful for his pastoral work with the Bible. Sometimes it's just helpful to have an older believer take your hand and walk you through the valley. We tend to get tired on this long walk, and Peterson feels like a dad to me, getting down on my level and helping explain his way of looking at truth. I'm so grateful for him and his efforts.

This morning I held my beautiful new copy of The Message and hugged it to my chest. It felt so good to have a friend for the journey. I needed that this week.

Anyway, as I was rereading Micah in Peterson’s language, I caught some nuances of the minor prophet that I had never understood before. I wish I had room left to unpack those here. Maybe tomorrow. For now, this post is too long already.