Sunday afternoon, and I’m sitting on a picnic table under an open shelter at the local state park. I’m up on a hill that looks down on the lake, watching a bunch of people messing around in the water. Maybe fifteen preschoolers are held afloat by inflatable arm rings, and they are bobbing in orbit around their parents like Jupiter’s moons gone wild. The older kids are playing shark, sitting on each other’s shoulders, and dunking one another under the dirty green water.

If I were their mothers, I would be terrified about somebody drowning or getting a brain amoeba; but these are women who wear big sunglasses and tank tops while smoking cigarettes; they throw their heads back and laugh so easy. Some folks are able to live fully in the present, and they are probably healthier than I am because of it.

Under a tree shade a little way out from the water, a couple is sitting on a blanket, putting suntan lotion on each other. They’ve been going over the same spots six or seven times, kissing every few seconds, hugging and fondling. All these people are sitting around them, and they don’t seem to mind the audience a bit. The guy is wearing a doo rag and the girl has dry blonde hair grown out a couple inches from dark roots. They’ve got to be all sweaty in this heat. He's too pink, she is too burnt, and they are both too soft to win any beauty competitions, but they are each the whole world to the other this afternoon, and I'm glad those little kids in the water aren’t paying too much attention to what’s happening on the land.

I used to despise July, but over time I've grown to love it even better than spring’s shy, pink graces or the sad, sweet, cinnamon longings of autumn. July is heavy, lazy hot. It makes your joints loose. The leaves are hanging down from their trees trying to get spread out from one another, wilted and soft like the skin on the back of the hands of a middle-aged woman who has just finished a full sink of dishes. Wasps and grasshoppers rise in little whirring motions out of the tall grasses, and when a kid runs through them it’s like the earth is throwing confetti up at the sky.

I know that if I sit here long enough this place will tell me what it’s saying. Robert Capon once devoted an entire chapter to the cutting of an onion, and his ideas have changed my outlook on almost everything since. He urges the seer to take his time: “As nearly as possible now, try to look at it as if you had never seen an onion before. Try, in other words, to meet it on its own terms, not to dictate yours to it. You are convinced, of course, that you know what an onion is. You think perhaps that it is a brownish yellow vegetable, basically spherical in shape, composed of fundamentally similar layers. All such prejudices should be abandoned. It is what it is, and your work here is to find it out."

Plato looked into the heavens for forms that would explain the earth, but his disciple, Aristotle, chose to look at the earth to understand the heavens. A balance is wise, I think. Both are necessary. Still, the willingness to see what's close has a lot to do with why Flannery O’Connor was such a good writer. It also explains why my friend Carey Pace digs photographic wonders out of whatever her kids happen to drag out in the kitchen today. Seers get down on their knees and explore a thing, because they know art isn’t about running off to grand places to find grand things, it’s about going inward and inward, into what’s already here, until you find out what the world has been telling you all along. Looking at details is humility, and it allows a disciple to recognize the Messiah when he shows up in Bethlehem or sometimes even in the middle of Wal-Mart.

A child is screaming hysterically. I think he has water up his nose. His big sister and brother are making a ring around him splashing as hard as they can, and he is mad that they aren’t empathetic. He has always been the baby and protected. Suddenly, he decides to smack the lake back at them until (haha!) he understands that he is both small and fierce. At once fury dissolves, and everyone is laughing, because all three kids are strong now, and that is camaraderie, which is something to celebrate. Their mother missed all of it, which was alright, because sometimes children need space to learn things instead of being refereed.

A new woman has entered the lake to swim. I didn’t see her until just this minute. Up until now, everybody in bathing suits has just been regular people, too white, too fat, wearing suits that look like they were bought two years ago with elastic that looks like it’s about to give up the ghost. But this woman is a thin, tan blonde in a firm coral bikini. She keeps tugging at the tied string that runs around the sides of her hips, but that looks like more of a habit than a necessity.

Every few minutes she bends over toward the children to run her fingertips in the water. She is a nympth, a transcendent wonder of the peasant gene pool. She is standing smack in front of the kissing couple on that blanket, but they aren’t kissing now because the man is leaning away from his woman, elbow planted way down into his knee so he can watch the bikini in the water. With the other arm he’s drinking one of those tall canned beers.

The woman on the blanket is angry. She angles her body away from him even while their rumps are still touching at the sides. He leans the other direction. They divide and divide, getting their spines to about a 45 degree angle before the woman on the blanket decides to change strategies and lie on her back with her glory up to the sun. As if on cue, the skinny nympth moves out of sight, and the boyfriend comes to himself and chooses to bless what he has been given instead of what has been taken away. All is forgiven. I don’t like to see them kissing, but I’m glad the pretty girl didn’t win.

A breeze is picking up because it’s about six thirty and the hot can’t hang in these mountains very long. That breeze is catching up the hair fallen down on the sides of my face, and it cools the sweat rolling down my back. I've been with people too much lately. My husband kicked me out of the house a few hours ago and told me to find somewhere quiet to settle down.

Lately I've been all stirred up about the rotten things happening in the world. Getting outside can do me some good when I get like this, but I don't know if it will today. I tried to read but couldn't focus, so I turned the speaker on my Kindle app and listened to a computer voice offering up Tim Keller’s thoughts on suffering. Keller knows the world is broken, but he says even if I fight like mad, I can’t change everything that's wrong, because sin's got itself all woven into everything.

He writes, “[p]ain and evil in this world are pervasive and deep and have spiritual roots. They cannot be completely reduced to empirical causes that can be isolated and entirely eliminated. As Hamlet said, 'There are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy. . . .' Perhaps even more to the point is a line in J. R. R. Tolkien’s novel The Lord of the Rings : 'Always after a defeat and respite, [evil] takes another shape and grows again.' No matter what we do, human suffering and evil can’t be eradicated. Even when you put all your force into stopping it— it just takes another form and grows in some new way. If we are going to face it, it takes more than earthly resources.”

Every penny in my pocket says “In God We Trust,” but the older I get, the more I see how often we don’t, neither the atheists nor the religious people like me who freak out and yell that everybody needs to trust Jesus and stop ruining my country. I need to learn to believe more, fight smarter, and fear less.

Besides all this, my oldest son is leaving for college in a few weeks, and the countdown makes every word we speak in our house feel so strange. I keep waking up at night with a feeling like he's two-years-old and lost in a department store. He's tall, muscular, wise. He's ready, but I'm not sure I am. Like everything with the first kid, I’m letting this become too big of a deal. He told me a few days ago, “Mom, do you realize you are bringing every conversation back to the dangers of substance abuse?”

It’s not that I don’t trust him, he’s a great kid. I just keep wanting to tell him something to settle my own nerves. These last few days feel like cramming for a test, and I want to write the answers to life all over him... not that I know all the answers to life, but I want him to have them. When he's at home, I'm gravitating around him, trying to make him sandwiches and finding excuses to sit close by. I’m going to miss him so much.

The woman on the blanket just stood up to wave at two kids in the water. She yelled and told to get over near the bank because there are jet skis coming. She’s a mother. I wasn’t expecting that.

There’s a blue chalk drawing on the shelter concrete. A child made it. There are six circle bodies drawn with six circle heads on top of them, then there’s another big circle drawn all around all of that, like children draw to signify that this all makes a family. Every child I've ever known has drawn families this way. It’s universal kid language. There is also one body drawn halfway through the large family circle, and I wonder who was meant by it. I wonder if that’s somebody who died, or somebody who got remarried, or somebody who grew up and left home for good. I want to find some blue chalk and fix that drawing so everybody gets in.

Have mercy, the couple on the blanket is rolling around. I mean it, they are wrestling in full daylight. The man is on top of her, and I see an arm flailing. She’s laughing, so I sit still, but other people are staring. They've been drinking too much and are making a tangle.

When they finally stop, they both stand up and shout at the kids in the water again. I realize that one of the kids is a teenage girl swimming with her boyfriend, and that those two are front to front, and the fella has lifted the girl up, carrying her. The momma tells them both to cut it out, then stands up and adjusts her shorts so she can take a few selfies before she sits back down.

There’s a walking trail that runs near the water, and people are making miles on it today. A young couple comes pushing a stroller. The mom is wearing her baby weight still, and it suits her beautifully. I’m not being kind, she’s radiant with maternity. Her head is wagging from not sleeping nights and her ponytail is a mess, but Dad is grinning and proud. I see her come up on the swimmers, and she’s panting, cheeks flushed. I can tell she doesn’t realize how beautiful she is, because her shoulders fold in like she’s ashamed of herself. Meanwhile that baby’s got his fat legs sprawled out wide and white, and he’s passed out from a belly full of milk, and the sunshine, and the motion of the stroller wheels. Dad doesn’t even notice the other women because he’s trying to make sure the other trail walkers get a good look at the child he helped make. I don’t blame him.

Two men with a little groomed dog. One swings his arms a lot while he’s talking and he walks kind of pinched in the back. The micro dog is leading both of them, and they wait for the pup to pee anywhere and sniff anybody he wants. I get judgmental and think that I'd make that dog mind a little better if he were mine.

An athletic girl in a yellow tank top walks on strong, brown legs. I remember that I need to start exercising.

Retired guy on a bike too small for him. He’s dressed up and wearing a helmet. Probably an engineer.

The shadows are starting to get longer.

Here comes an older couple. The woman is wearing a visor, a bright floral top, and Bermuda shorts. She is trim and looks like the sort of person who would cut sugar and salt in recipes and plan for when celery is on sale. She’s walking a few steps ahead of the man, and she seems comfortable there. Her husband looks a little lost, but he has wondrous round belly, round nose, round cheeks. I like him. She is alert and angular, as if she's been figuring things out for both of them all their lives. She carries her hand in a point and directs his eyes and thoughts with a finger. I suddenly realize that she was a teacher, probably fifth or sixth grade. He has a baseball hat pulled way down over his eyes.

I look down near the water and see that the blanket couple is packing up their stuff. They take it slowly, standing with their hands on their hips. The weekend is over. We’re all delaying, and no matter what differences there are between us, as evening falls on the park, a communal empathy starts to make everyone gentle with one another.

I missed church this morning, but this time of the day makes almost the same feeling I get Sunday mornings during the greeting when everybody turns around and says, “Peace of Christ to you," and suddenly you smell everybody’s aftershave and fabric softener because people are reaching across one another to make a welcome. I’d like to watch that greeting from the ceiling someday. I’d like to look at all the stillness, all the obedience, all the standing and sitting, quicken up into that glorious awkward flutter of fellowship.

Another Sunday gone. Another Sabbath that we all took to rest, and to love, and to swim, and to kiss. An afternoon to catch a breath from fear. A walk. A nap. An hour or two away from the noise. I don’t want Sunday to end. I don’t want July to end. I don’t want this stage of life to end, but time moves on and on. The peace of Christ to you.

- - -

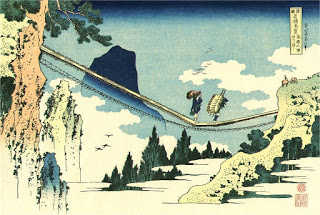

Painting: "Swimmers, Javea" (Detail) by Joaquin Sorolla (1905)